Distinguished ladies and Gentlemen, I know not what qualifies me to be your choice of speaker at this maiden event but believe me I am here with delight because my recollections of, and my interactions with the Body of Benchers fill me with nostalgia.

As a young Law Graduate applying to the Nigerian Law School, the fear of the Body of Benchers was the beginning of wisdom, back in the 1980s when I had cause to interact with the body.

It was not “fear” represented by “dread” on the contrary it was “awe inspiring” “fear” of the achievements of the members in and out of Law Practice and their stature as giants of our profession and society; men and women of high repute and integrity.

Indulge me by allowing me to recall 3 (three) of them and thus set the stage for the focus of my intervention today.

THE PAST

The first is the late Chief Debo Akande, SAN who was my late father’s friend who gladly accepted to have me undertake my compulsory Law office chambers attachment in his office at the Western House. Having supervised me for several weeks it was easy to make a personal reference and recommendation about my suitability for the call to the bar.

And the fundamental question is this: How many benchers today have had the personal experience and observation of the persons they sponsor for a call to the bar?

And this takes me to my second Bencher, T.A.B OKI, SAN also of blessed memory. He was my second sponsor. He did not know me, but had known my father and grandparents for many years. He was a very reluctant sponsor and made me aware of it.

He refused to sign my form when my father presented it to him. He insisted I must come to his office on Kofo Abayomi in Victoria Island, which I did.

At his office, he interviewed me as if I was seeking employment with him.

He made it very clear that he was gambling on me only because he knew my father very well and extracted an undertaking from me to always try to be of good behaviour according to him, “like my father.” I readily gave the undertaking in writing and the experience has never left me.

How many Benchers today sponsor candidates for calls to the Bar that they have never interacted with?

The third Bencher in focus is Mr. Webber George Egbe, QC, SAN also now of blessed memory. He was the chairman of the Body for 1988 – 1989. He presided over my call to the bar on the 2nd November 1988.

In the speech he delivered, he said many things that I do not now remember. But he said one thing which I have never forgotten and it has remained with me as a useful tool of life.

He spoke about the power of self-discipline. The core of the message was that from primary school through to that night of our call to bar, we had been under some form of imposed discipline by parents, guardians, teachers, lecturers and persons who stood in loco parentis.

On that night of our call to the bar he said that the “yoke” of imposed discipline had been lifted but that we needed to remain disciplined to progress in life and that the hardest discipline was self-imposed discipline which each of us must now find.

I have chosen to start my intervention today by these stories in an effort to graphically illustrate the profundity and importance of one of the statutory functions of the Body of Benchers, which is to regulate the admission of persons into the legal profession and to exercise disciplinary jurisdiction over legal practitioners as prescribed in the Legal Practitioners Act (LPA), Cap L11, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004.

It is a big responsibility of Human Capital Development and nation building that is not to be undertaken lightly or with levity.

If anyone of unsuitable quality, character, integrity, or competence slips through the cracks, a poor-quality lawyer has been made, a potentially poor-quality Law Teacher, Prosecutor, Judge, Legal adviser or Law Officer.

A grave danger would have been created for the system of Administration of Justice where the stakes are very high in terms of Lives and Livelihoods.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the events I have recalled about the three gentlemen about whom I have spoken relate to an era around 1988 (37 years ago) a whole generation. At the time when I enrolled at the Supreme Court which was then in Lagos on the 3rd November 1988, I was No. 10,550 on the roll of the Supreme Court.

From my inquiry, the Nominal Roll of the Supreme Court now has 146,255 lawyers.

The theme of this lecture is “HALF A CENTURY OF THE BODY OF BENCHERS, THE PAST, THE PRESENT, AND THE FUTURE OF MAINTAINING THE ETHICS OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN NIGERIA.”

Permit me therefore to adopt my short stories as representative of the past in the discussion of the past, present and future of the Body of Benchers.

Inherent in those 3 (three) stories are practical illustrations of the work of the Body of Benchers through its members, manifestly concerned about issues of integrity and character of persons who pass through them to be admitted to the Nigerian Bar and unleashed unto the larger society.

But the pertinent question to ask the layman is who are these people who call themselves the Body of Benchers and what do they do?

These are questions the Body must consciously attempt to answer by engaging in what I call Street Level conversation.

Given the quality of the audience here today it will serve no useful purpose for me to attempt that answer in any detail in view of the constraints of my time.

For the layman who uses a search engine to look for the Body of Benchers, one would come across a site named bob.goo.ng. That site relates the history of the Body to the work of the Unsworth Commission constituted by Prime Minister Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. This would give the impression that the Body came into being in the 1960s and should be commemorating its sixth decade of existence. This is in stark contrast to the notice of the body at this event to review its past, present and future in half a century.

This narrative must be reconciled with the account contained in the autobiography of Justice Olakunle Orojo at page 101 thereof where he said about the founding of the Body of Benchers that: –

“In my annual report to Council of 1967, I discussed this matter and recommended the institution of a system of “dining” to enable students meet members of the Bar in an informal way to acquire those intangible attitudes of a Lawyer which can hardly be taught by theoretical lectures…This eventually led to the establishment of the Body of Benchers and the integration of the Dining into the system in 1973.”

It suffices to say, as a reminder to all who are present, that this body is the Regulator and quality controller of the legal profession. If quality control fails the society is in trouble.

I believe it was in the popular case of LPC v. Abuah which we are all familiar with that the pioneer Chairman of the Body of Benchers, Sir Adetokunbo Ademola restated the onerous responsibility of those charged with admission of new lawyers when His Lordship said that: “By enrolling them we present them to the public as men the public can with confidence employ to carry out the duties and responsibilities appertaining to their all-important office. We therefore owe it to the public to see that members of the public are not exposed to risks in their dealings with these men.”

It is of course important to mention that the body did not always exist. Prior to its establishment, applicants who had qualified and had been called to the Bar in other jurisdictions were enrolled in the Supreme Court.

This is the reason our first-generation lawyers had two dates; the date of Call to Bar and the date of Enrolment in the Supreme Court. It was in the late 1960s, after the establishment of the Nigerian Law School, that the idea was conceived to establish a body to be responsible for admission of applicants to the Bar in Nigeria before their enrolment by the Supreme Court.

This led to the promulgation of the Legal Practitioners [Amendment] Decree No. 45 of 1971 which formally established the Body of Benchers fifty-four years ago under the leadership of the then Chief Justice of Nigeria, Hon. Justice Adetokunbo Ademola.

But many things have changed.

THE PRESENT

As we move from the past to the present, we must acknowledge that the Supreme Court, in which I registered in Lagos, is now in Abuja, the Nigerian Law School which was only in Lagos now has schools in Abuja, Bayelsa, Kano, Enugu, Yola, and Port Harcourt in addition to the Lagos School.

The world itself has changed and a survey will reveal to us that our Law School is now graduating about 5,000 students averagely per annum. This is now about half of the 10,550 lawyers who registered in Nigeria when I enrolled in 1988.

There are now 146,255 lawyers on the nominal roll. There is also good reason for us to be concerned about public perception of our administration of the justice system in which lawyers produced from the Law School and admitted to the Bar by the Body of Benchers play a prominent role.

If this is a fair picture of the present, what should we do about the future? From where will reformists like those who spearheaded the Birth of the Council of Legal Education, The Nigerian Law School and the Body of Benchers come; one might ask?

THE FUTURE

My answer is that many more of them are in this audience and so this lecture provides a unique opportunity to start the conversation. Therefore, within the framework of the theme past, present and future selected for this conversation, I wish to ask the reform minded persons in our midst whether the time has not come to re-think and re-make how we train lawyers in Nigeria?

Given the public concerns about the administration of justice has the time not come upon us to separate and specialize the training of solicitors from Barristers or advocates?

The focus on Benchers/Advocates is particularly important because it is the output of their work in the courtrooms that the public is overtly concerned about.

Is this not the time to also look in the mirror and at the current Law School curriculum and ask ourselves what kind of advocate we can train in 1(one) year with a theoretical outlook and insufficient time or infrastructure for CourtRoom practice and exposure.

Put differently, can the current theoretical exposure and limited court and chambers attachment deliver the “…intangible attitudes of a Lawyer…” that Justice Orojo spoke about as the reason for the establishment of the Body of Benchers.

Permit me to tell you yet another story.

It is a story that hugs the controversy of whether law practice is a trade or a profession. That debate has been had by many intellectuals, and the “profession” appears to have overcome “trade.”

What is undeniable is that the law profession, especially the Barrister’s work, is rooted in norms, usages, traditions, and culture, all of which are best learned in practice rather than in a classroom.

The story of Owoblow is empirical proof of the point.

It is the story of a graduate not of law who, for lack of employment, took up the job of a law clerk back in the 1990s.

His job was to file and serve court processes. He was trained to draft affidavits of service and to depose to them and get court processes into file.

From time to time, he accompanied lawyers to court. In no time, he knew the names, citations and locations in the office library of all the major cases on injunctions, stay of execution, summary Judgment and the major legal issues that dominated headlines in the 1990s.

On one occasion as senior associate, when l reviewed the work done by law students on chamber attachment and asked why he had drafted a document in a particular way, the response I got was that it was Owoblow that taught him to draft it that way.

I was outraged that a law graduate under training in the Nigerian Law School was taking instructions from a non-law graduate who had not been to law school.

But the reality was that Owoblow was training by daily practice. He knew the Bailiffs Section, Probate Section, and had become comfortable with completing the forms for Lawyers in chambers to sign.

In the event, the chamber advised Owoblow to return to university, where he got a law degree and from there to law school.

I can say that he is now one of us, and was very well trained.

Given this story, the question to ask is how many of the over 5,000 lawyers were ready for courtroom work the following day.

Some of the best lawyers and Judges of repute produced in this country walked paths similar to that of Owoblow; by serving as court clerks or Registrars, before embarking on formal training as lawyers.

Clearly, there is a lot to learn from this about the gaps in our training of lawyers. What we seemed to have focused on is the academic part. The Bar Standards Board which regulates the profession in England and Wales moves beyond this by stipulating vocational training and pupillage (after the academic training) before a barrister can appear in court.

We must ask ourselves whether those who just want a law degree to proceed to other occupations should bother to go to the law school.

We must also question the continued relevance of the law school as a training institution and its efficacy to train over 5,000 students into proficient advocates.

I would recommend that post university training of solicitors and advocates be left now and in the future to law firms to be accredited nationwide for that purpose, while the Law School under the aegis of the Council of Legal Education remain an examining and certification body, separating Solicitors examinations from that of Barristers.

In the latter case that is where the scrutiny of the Body of Benchers should be focused – those Barristers to be admitted to the Bar.

My suggestions are not perfect, but I believe that the time for change and reform was yesterday, if we are to remake the system of administration of justice. We must start with the people who get to operate the system.

Competence is key and it is from competence that we can set standards; when we set standards, non-compliance is easily detectable and sanctionable.

I regret to say that today one is hard put to see the “wood from the trees” in the difference between incompetence and misconduct in some judicial outcomes.

The skill of Barristers and those of them who become Judges and their level of competence must account in part for why cases based largely on documents still take several years to try and decide in spite of many fast-track efforts.

Before I conclude, I must be on record to state for those who do not know that in addition to its recommendation of persons to be called to the bar, the Body of Benchers also has responsibility for discipline of legal practitioners who are not judges.

This is a very important responsibility and the future of the profession and by extension the Body of Benchers depends on how this responsibility is discharged.

Put differently, when quality control fails and a bad product enters society, what is the power of recall or remediation that the Body of Benchers exercises to remedy the situation?

I am aware that the Committee that discharges this responsibility on behalf of the Body – the Legal Practitioners Disciplinary Committee – has tried and dispensed with some high-profile cases.

I am glad to learn from the Chairman of the Body of Benchers, Asiwaju Adegboyega Awomolo, SAN that there is going to be a public presentation of the Reports of the Directions of the LPDC today immediately after this lecture. This is commendable.

But the question to ask is whether the average Nigerian thinks that the Committee has done enough.

The public space is full of reports of multiplicity of suits and suggestions of forum/fora shopping aided by legal practitioners in manifest abuse of the judicial process.

What does it take to bring these lawyers to book and what kind of consequences are they subject to?

A Nigerian colleague who had a multi-jurisdictional practice once told me that he was presenting a case in the UK when the presiding judge asked if he was not aware of the recent decision of the UK Appeal Court on a similar point.

Needless to state, the judge stood the case down for him to go to the library to update his knowledge and he returned to withdraw and abandon the argument.

According to him, the judge would have referred him to the UK disciplinary Tribunal and he could lose his licence to practice if found culpable of wasting judicial time.

Is the standard that high here and what are the steps that must be taken to raise the standards?

When is the LPDC going to set and enforce new rules for Television Lawyers?

When can a judge unilaterally refer a petition for unethical conduct in the course of trial against a lawyer? And what are the expanding frontiers that lawyers and clients have for holding judicial officers accountable without being in contempt of them?

As the Regulator, does the Body of Benchers issue a written Code of Conduct for Barristers (and Solicitors), or are we still guided by what was taught in the professional ethics class in the Law School?

Are there laymen, such as non- lawyers or non- Benchers assisting or contributing to the work of the Body by her various committees?

If there are none, is there something to be gained from involving some of the most vocal critics of the justice system into committees of the Body of Benchers if only on an adhoc basis.

To the extent that public confidence is critical to the reputation of the system of administration of justice, l think these are matters that require serious consideration.

In the course of preparing this speech, my colleague, Olanrewaju Akinsola, sent me a monograph containing a speech titled, “The Future of the Bar in Nigeria,” somewhat similar to the theme of this meeting by the Body of Benchers.

The speech was published in the Nigerian Bar Journal (I don’t know if it is still published).

It was delivered at the time when according to the speaker “… there are about 600 members of the Bar in Nigeria.”

Apart from the sagacity of the speaker, who was none other than Sir Adetokunbo Ademola, the then Chief Justice of the Federation and first Chairman of the Body of Benchers, the words of the speaker ring true today as they did then about the role of Lawyers.

After pointing out the role that lawyers like Sapara Williams, Egerton-Shyngle, Sir Kitoye Ajasa and Sir Adeyemo Alakija had played in the struggle for independence he then proceeded to say amongst other things that :-

“Now that you members of the Nigerian Bar Association have for the first time met in conclave, it is not surprising that the minds of many of you should turn towards the future of this country …

By your actions and by your ingenuity, the Bar can certainly wield a great influence in shaping the future of this country…The greatness of any country is in its legal system.”

I will add my own words to those great words by saying that a poor Bar portends a poor future and a good Bar portends a better future.

And this must be the imperative for members of the Body of Benchers not only to keep their hands firmly placed on the Regulatory door of admission to the bar, they must lead a crusade of urgency to remove unsuitable persons and characters before they bring down the house.

In a speech l delivered at the Annual General Conference of Egbe Amofin O’odua in Lagos in June last year, I showed examples of how members of the bar affect the development of Nigeria in ways that many seemed surprised to hear.

I will share a few of them quickly:

For example, the Geometric Power Project in Aba, was held up in court for years before my assumption of office in 2015 as Minister of Power during which my Ministry worked with the office of the Vice President to successfully broker an out-of-court settlement.

Similarly, the recently completed 700 MW Zungeru hydro-power plant in Niger State, was held up by a court injunction obtained by a legal practitioner suing for his commission with local partners, but the injunction was against the lender, China Exim Bank and lasted for 3 years before I took office and led the negotiation of an out-of-court settlement to unfreeze the deployment of millions of dollars meant for the project.

Another real-life example will help to explain the point. For many years, Lagos had only one major mall of repute at the Lekki mall developed in Oniru Estate.

In the course of my public service tenure, the Lagos State Government was looking to the same investor to build and open the Ikeja Mall. The land which hitherto was used as bailiff’s warehouse has been acquired and an alternative provided.

Reluctantly, the investor agreed to build the Ikeja Mall and nobody challenged them until opening day when some persons with lawyers behind them sought an ex parte injunction to stop the mall from opening, claiming to be the owners of the land on which it was built.

Please note that for many years, these people never challenged the judiciary for using the land as a bailiff’s warehouse, when the development and construction of the mall took place over 2 years they made no challenge. They waited until the opening day when goods had been supplied; people employed, and when customers were due to arrive before coming to assert their nebulous “right”.

To the immense and eternal credit of the Lagos judiciary under the leadership of Hon. Justice Ayo Phillips, Chief Judge, which had a clear understanding of the investment drive of the executive, no injunction was granted; in lieu thereof accelerated hearing of the claim was ordered and the mall has continued to thrive perhaps because there was never any right to land in the surreptitious injunction seekers.

But for that judicial outlook it may well be that the opening and operation of the mall and the livelihoods it supports today will be a mirage trapped in unending litigation.

I know of an investor who for eleven (11) years has been waiting for a court dispute to end so he can build a multi-storey office complex.

Ladies and Gentlemen, our judicial system which is one of the most revered judicial systems in the commonwealth is facing scrutiny under a large microscope.

The reasons for scrutiny are not far-fetched. Some of the outcomes from the legal system raise more than an eyebrow.

If the outcomes raise concern, certainly we must interrogate the input, which is the quality of persons admitted to the Bar by the Body of Benchers.

This meeting is our golden moment to start a new journey for the Nigerian Legal system by demonstrating that there are internal self-correcting mechanisms that ensure that the dispensation of justice is speedy, credible and reliable.

By reforming the training process of persons called to the Bar (as distinct from Solicitors whose work is not so much public facing) we can secure a prosperous future for the legal profession that is anchored on sound ethical foundations of competence, character and integrity.

This is the hard but necessary road of the journey to restoring public confidence in the Nigerian legal system and profession.

Thank you for listening.

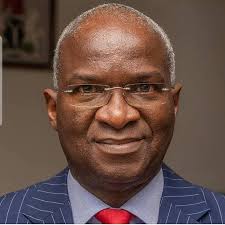

.His Excellency, Babatunde Raji Fashola, SAN, delivered this speech on the occasion of the Body of Benchers Annual Lecture (BOBAL 2025) on Wednesday, March 26, 2025 at the Main Auditorium, Body of Benchers Complex, Idu, Abuja, FCT.